0

12

2

While for the longest time, scientists and philosophers argued whether animals are capable of emotions and empathy, some researchers set out to prove their point. And with the likes of Koko the Gorilla, it’s hard to deny that animals are capable of feeling and expressing human-like emotions.

Scientific research reveals that rats are capable of empathy, even with strangers

The research that spanned over few years and involved several experiments was headlined by Professor of Neurobiology Peggy Mason who, after a 25-year focus on the cellular mechanisms of pain modulation, switched her focus to the biological basis of empathy and helping.

The first study, that was started in 2007 and published in 2011, focused on whether rats help each other in distress under different circumstances. Professor Mason explained that it was her colleague’s Inbal Ben-Ami Bartal’s idea and she was happy to be invited to the project (she later dedicated her entire lab to helping and empathy). ” I remember that we knew we had “it” when Obama nominated Sonia Sotamayor in 2009 and made a big deal out of her empathy,” she explained.

The basis of the research was that rats showed basic emphatic tendencies, like when one baby cries, other babies cry. However, they wanted to dig deeper and see if rats would go beyond emotion-contagion. It would require for a rat to downplay its fear from emotional contagion in order to help the rat in distress.

The basis of the research was that rats showed basic emphatic tendencies, like when one baby cries, other babies cry. However, they wanted to dig deeper and see if rats would go beyond emotion-contagion. It would require for a rat to downplay its fear from emotional contagion in order to help the rat in distress.

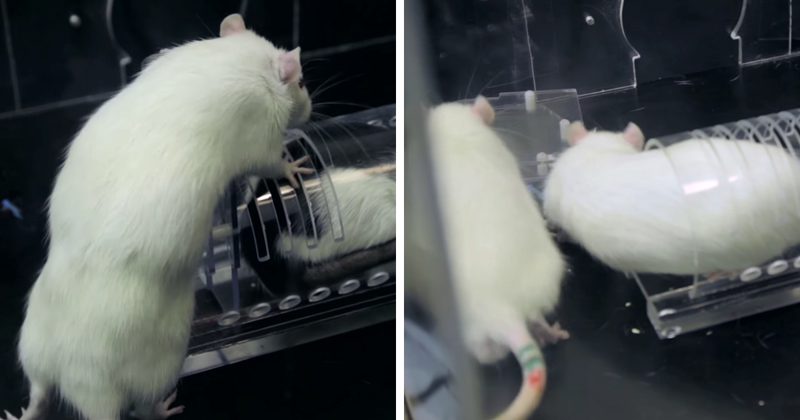

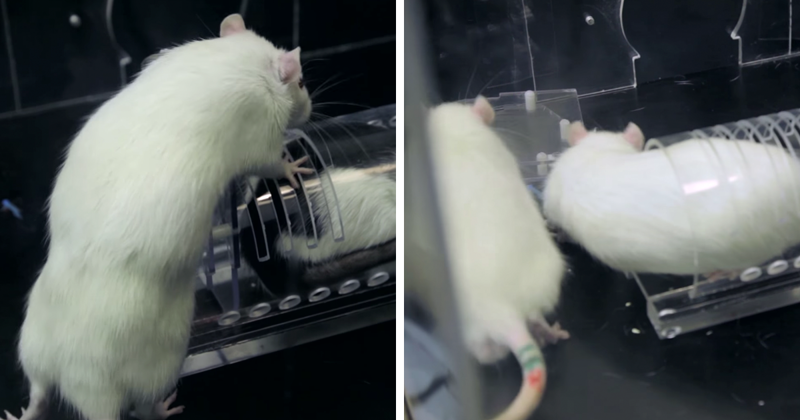

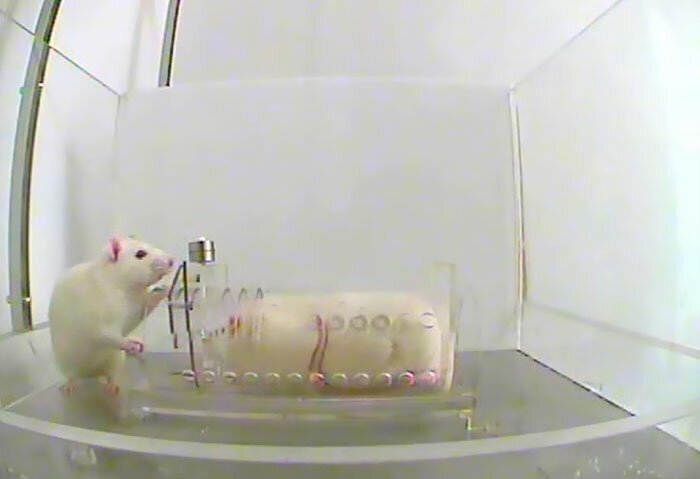

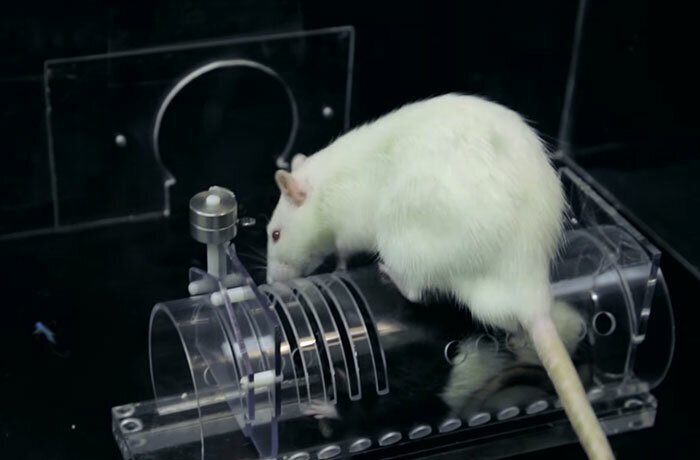

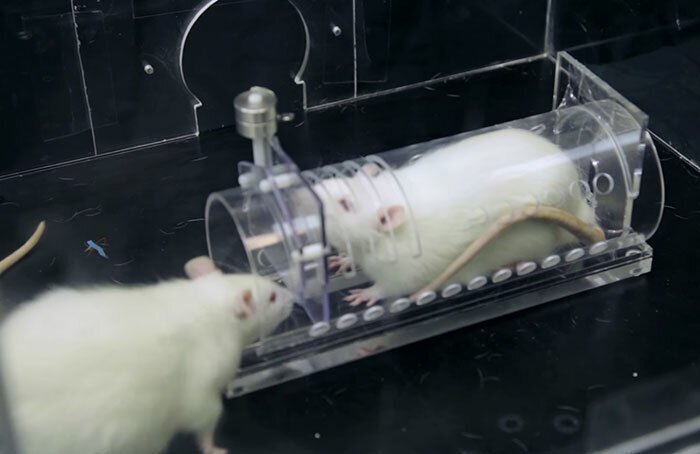

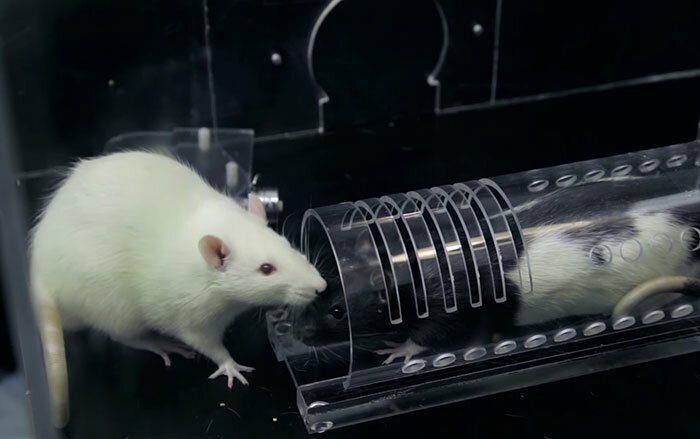

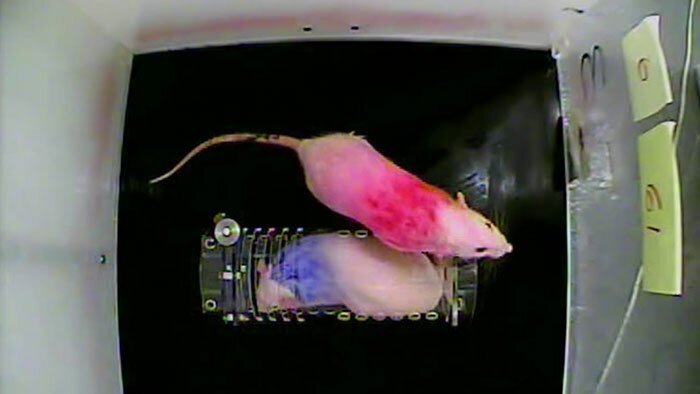

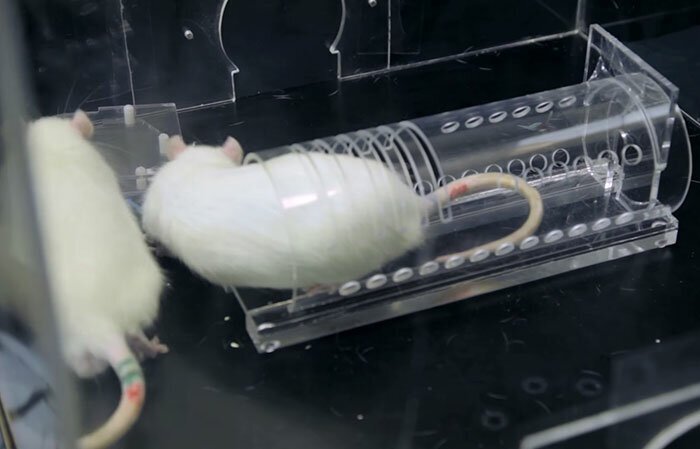

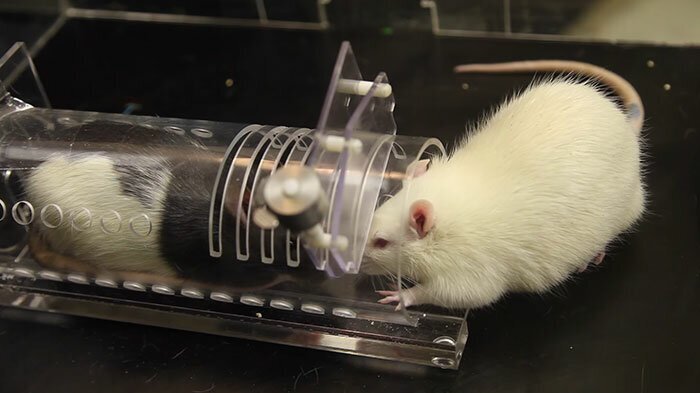

Together with Inbal Ben-Ami Bartal and Jean Decety, professor Mason set up an experiment where one rat was trapped in a tube while its cage-mate is released into the “arena” where only the free rat can open the door of the tube. What the initial research revealed is that within a short period of time, the free rat tried to figure a way to help out its cage-mate. In 12 days of testing, the free rat finally figured out how to open the door and released its friend within the 3-6 days, proceeding to jump around and follow the now free rat. It appeared as though they were celebrating!

During the next few days, the free rat, once put in the “arena” almost immediately releases the trapped cage-mate. The researchers pushed their experiment one step further by placing 2 containers in the space, one with the trapped rat and the other with 5 chocolate chips. The team behind the study was shocked when the free rat not only opened both containers in no particular order, but also shared the treats with the liberated rat instead of opening the container with chocolate first and claiming all the goodies for itself.

The first research concluded that releasing its trapped cage-mate was on the same level as getting a chocolate treat in the rat’s books. The researchers also argued that it was the trapped rat that elicited such behavior, as the free rat would not open the door if the tube was empty or contained a toy rat. It would also open the door even if it wouldn’t get the chance to be reunited with the trapped rat, meaning that it didn’t just merely want to play with it.

Professor Mason continued her research into empathy and rats and presented some surprising results in the upcoming years. Her later study, conducted in 2014, showed that rats are “selective” about whom they empathize with. When introduced to a different, unknown strain of rats, the free rat would not free the trapped rat. The research yielded the same results if the free rat was grown in isolation and wasn’t socialized even with its own strain of rats. What it basically means, is that if a rat has never seen another rat of its own strain, it won’t open the door. “We call this the switched-at-birth or Mowgli experiment,” professor Mason added. The research drew the conclusion that empathy is based on the rat’s social experiences, but is not limited to only the individual rats it knew, as the free rat would help a stranger rat if it was ever exposed to its strain.

To further prove her point that rats are driven by empathy, professor Mason ran another experiment where the free rats were given anti-anxiety medicine and because of it, they no longer set the trapped rat free. The researchers concluded that because the free rat could no longer feel stress and emotions by empathy, it wouldn’t understand what the trapped rat was feeling and felt no urgency to set it free. You can watch the videos below for a more in-depth explanation of the research, or check out Peggy Mason’s blog here. And if this research got you interested in neurobiology, you can also see the course professor Mason is teaching on Coursera.

Peggy Mason also informed us that they are continuing work on this study, with several extensions. “One experiment that we’re working on now is to see if we can make a rat familiar with a foreign strain of rat more quickly and differently than 2 weeks of housing,” the professor elaborated. The team wants to see is sharing a “dinner party” with plenty of treats will yeld the wanted results. “In general we have been interested in figuring out what it takes to make one rat familiar enough with a different strain of rat to be helpful to that strain,” she concluded.

Source:

Ссылки по теме:

- Vintage Style Astronomy Maps Made from Open Source Data of the Universe

- Scientists Discovered a New cat-fox Species Which Was Previously Believed To Be a Myth

- Scientists Are Amazed After Painting Cows In Zebra Stripes – They Get Bitten 50% Less Than Usual

- Scientist Bakes Bread From 4,500-Year-Old Yeast, Says The Flavor Is Incredible

- I Restore ‘Unrestorable’ Photos, And Here’s The Result